Novel by Charles Cumming, published by St Martin’s Press (2019)

The Moroccan Girl follows spy novelist Kit Carradine as he is recruited by British intelligence prior to his trip to a literary event in Marrakech. He’s tasked with finding the mysterious, and presumably eponymous, Lara Bartok, who was involved with Resurrection, a group that kidnaps and murders right-wing politicians.

I say presumably because there’s not actually a Moroccan girl in this novel. Bartok is Hungarian, and the only Moroccan women in this story are a couple of prostitutes, whose giggling and Snapchat butterfly filters ensure they are the intended girlish backdrop for the grown-up conversation of the men in their company.

Carradine also shares a brief conversation with a landlady, that, despite owning the building he is staying in, and despite his having seen her write, he suspects of being illiterate.

For a book that stifles and erases Moroccan women, it is infuriatingly titled (it was previously released as The Man Between in 2018). It’s clear from the book’s geometric cover, and blurb, which describes Marrakech as exotic and perilous, that Morocco’s role is to add perceived danger. I’m not sure precisely what makes Marrakech so perilous, perhaps it’s all the holidaying Europeans, or the English spies bringing their politics to its literary festivals?

Exotic metaphors in The Moroccan Girl are occasional, but exhausting. To Carradine, espionage was “a world that was as alien to him as a chapter in the Arabian Nights or the Berber poem passed down through the centuries and now repeated by an old, bearded man, seated on a tattered rug in front of him, taking coins from passers-by as he intoned his ancient words.” I needed a rehydration intermission just to get through that mystical nonsense.

Much like Kit Carradine’s character is described as “a foreigner’s idea of an eccentric Englishman,” the Arabs in The Moroccan Girl are a foreigner’s idea of clichéd Arabs, and excruciatingly so. There’s the prostitute in the pink jellaba, who offers Carradine a “bedroom look.” There’s the wealthy, upper-middle class characters whose actions are reduced to metaphors about carpets and souks. There’s the nameless “raggedy children.” There’s the educated man who has somehow continued to be employed in the capital’s sea port authority while believing it is “beneath his dignity to have formal dealings with women.”

We rarely get to hear from real Moroccans, but when we do, they are one-dimensional. It would be charitable to credit these views as belonging to Carradine, rather than the author, when we are shown little else to combat these stereotypical flashes.

In fact, the narrator participates in the perpetuation of misinformation. The minaret of Koutoubia Mosque is referred to as a “tower,” and we see a Moroccan give a “low bow,”(has anyone ever seen an Arab give a bow? We’re always in white, Western books bowing, but I have yet to see this pig fly).

We also learn how to tell the difference between Moroccans and other Africans: “He was African but did not appear to be local; he was too well-dressed and carried himself with the easy confidence and swagger of a European or American.”

Are we to believe that only white people have confidence, and Africans can’t have swagger of their own? Perhaps it’s a comment on Kit Carradine’s success despite his mediocrity. Every person the protagonist meets is enamoured or impressed by him, even when he completes the most basic of tasks. He frequently watches Moroccan women – presumably because he never talks to them – and sometimes he’s downright creepy, such as when goes to collect clothes for a woman he has just met (and is attracted to), and meticulously wraps her most treasured item in a pair of black knickers.

What, she doesn’t wear socks? Knickers are 75 per cent hole and nobody’s top choice for wrapping valuables.

I digress, because the white man’s mediocrity and presumption has me triggered.

To its credit, The Moroccan Girl successfully echoes extremist, dehumanising propaganda. The right-wing journalist who is targeted by Resurrection writes, “The immigrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean are the same insects already swarming over Europe… The only answer is to lock up every young Muslim man or woman whose name appears on a terrorist watchlist.”

Clearly, these are not beliefs that author Cumming holds or promotes. They are believable, Islamophobic statements made by a fictional right-wing journalist, who ends up murdered for her writings.

But we have to question the purpose and intention of including incendiary language, and a provocative martyrdom, in a wider narrative that doesn’t address the social stigma against Arabs and Muslims. The book provides us with context for how the once-peaceful Resurrection – which is, mercifully a European, not Muslim, group – descended into violent vigilantism, but the atmosphere of abuse that Muslims face is not explored or critiqued.

The lack of resolution for readers who face these abuses in their real lives transforms what could have been an interesting social critique into a novel that takes advantage of Muslims – in this case their struggle with Islamophobia – to further its narrative of danger.

There are minor believability issues within the text too, most of which would be unnoticeable to those unfamiliar with Morocco. But it’s suggested that Lara Bartok chose to hide in a Muslim country because “Almost all the women Carradine saw – locals and foreigners alike – had their heads covered with shawls or hats,” it’s worth remembering that Marrakech – that famously conservative party city – reaches 40 degrees in the summer and you’d be mad to go outside without a hat. But sure, people only cover their heads in hot Muslim countries. We’ll go with that.

What sets The Moroccan Girl apart from other reviews on Muslim Impossible is the unexpected absence of Moroccans. Despite only having been a spy for a matter of days, Carradine is infinitely more capable than the needy, incompetent local spy, Yassine. Beyond this character, Moroccans are relegated to passing acquaintances, while the story centres around white, Western characters in Morocco.

The Moroccan Girl’s gravest crime is its title, which implies a nuance, coverage and conversation that is entirely absent in this novel.

2/3

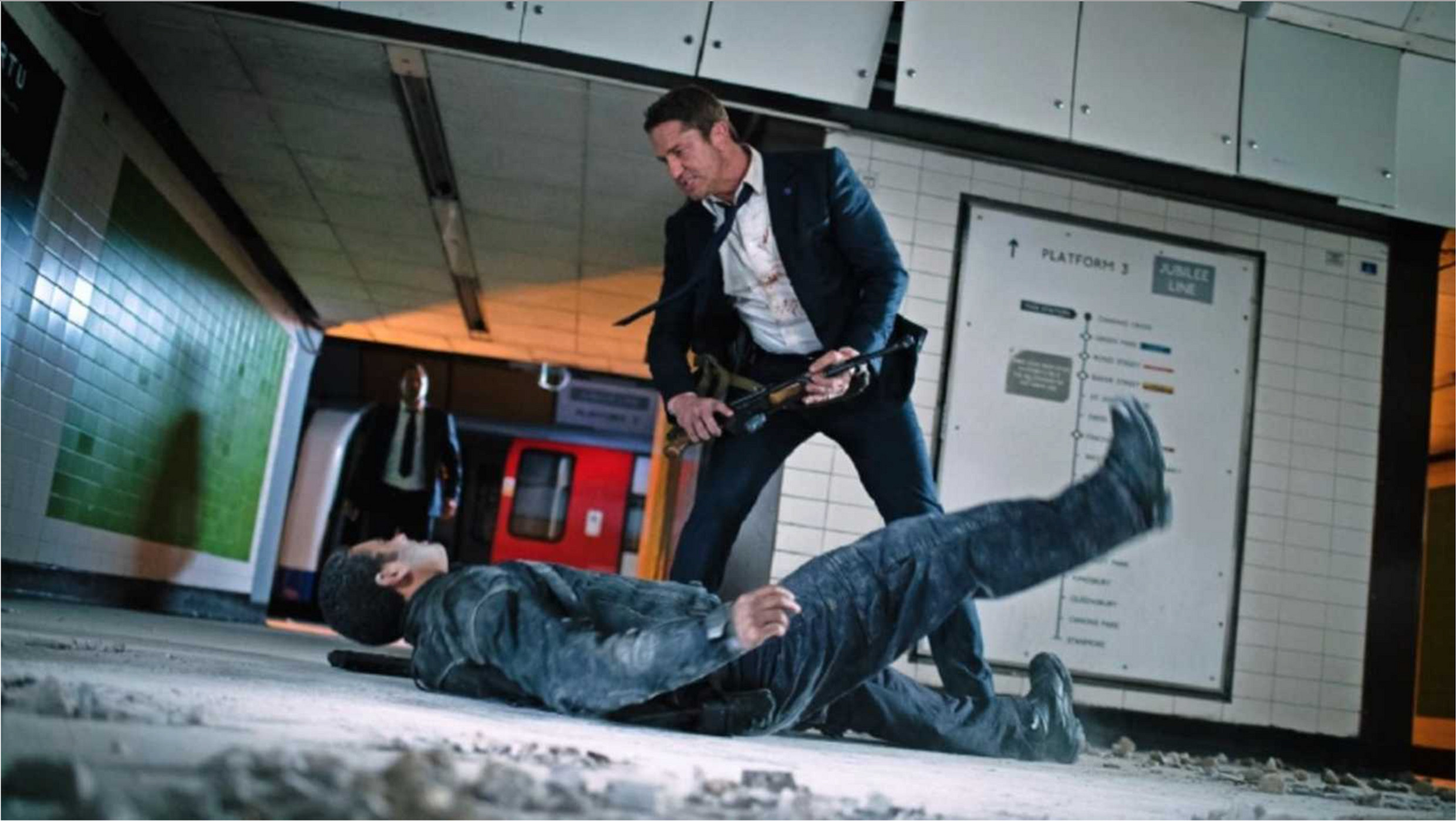

The Moroccan Girl receives two bloodied swords for the erasure of Arabs, and occasional exoticism.