Novel by Christine Mangan, published by Little, Brown (2018).

The Times described this debut bestseller as “unputdownable,” which – inane words aside – is the far greater fiction than you’ll find in this book. I put it down frequently, to take deep breaths, to shake my head, and to retrieve my eyebrows from my hairline.

Descriptions of Tangier are not just inaccurate; they are deeply exoticised. “Morocco. The name conjured up images of a vast, desert nothingness, of a piercing, red sun.” I don’t know who conjured this image but it’s time to revoke their magic circle membership.

Mangan’s depiction of Arabs is problematic, too. It becomes clear very early on that the setting for this novel is not to enrich a story with social nuance or to address the struggle for independence (it’s quite remarkable how you can set a novel in 1950s Morocco and manage to ignore its liberation movement). No, Tangerine is set in Morocco simply for the false mystique of ~Arabia~. Prepare to endure the cheap imagery of genies and the desert in the “arid heat of Tangier.”Again, this is a coastal city.

But don’t expect any meaningful interaction with Arabs. In Tangerine, Arabs are simply a tool to heighten mystery, and if they’re thrown under the racist bus to achieve that, at least that makes them putdownable. The first Arab we encounter is referred to as “The Mosquito,”(probably because it’s easier spell than Abdulwahhab), a title his character is forced to be complicit in and happy about in a way that no person – no, not even an Arab – would.

The only Arab of any significance in this novel is introduced a quarter of the way in, and his existence is purely to be the dark, menacing narrative tool to heighten tension for our white English heroine. He hisses, his lips curve and his eyes glint as he taunts the protagonist. This is a classic example of the promotion of white stories – even when they are set in Arab countries – at the expense, and dehumanisation, of Arab characters.

Because in this novel, Arabs are homogenised, even across countries. They are the “Rif women,”– frequently referenced, but only ever as a faceless, abstract group. They are “A crushing tidal wave of…locusts,” they conceal weapons beneath djellabas. They are too insignificant for meaningful characterisation, but worthy subjects of racism: “The natives are getting restless, my dear.” The prejudiced attitude of some key characters is never tackled, seemingly justified by the authenticity of the time.

Tangerine could have been a wonderful exploration of colonial attitudes during a historical political milestone. Instead, it is filled with lazy exoticism, geographical inaccuracies, and disappointing colonial tropes that go unchallenged by an irresponsible narrator.

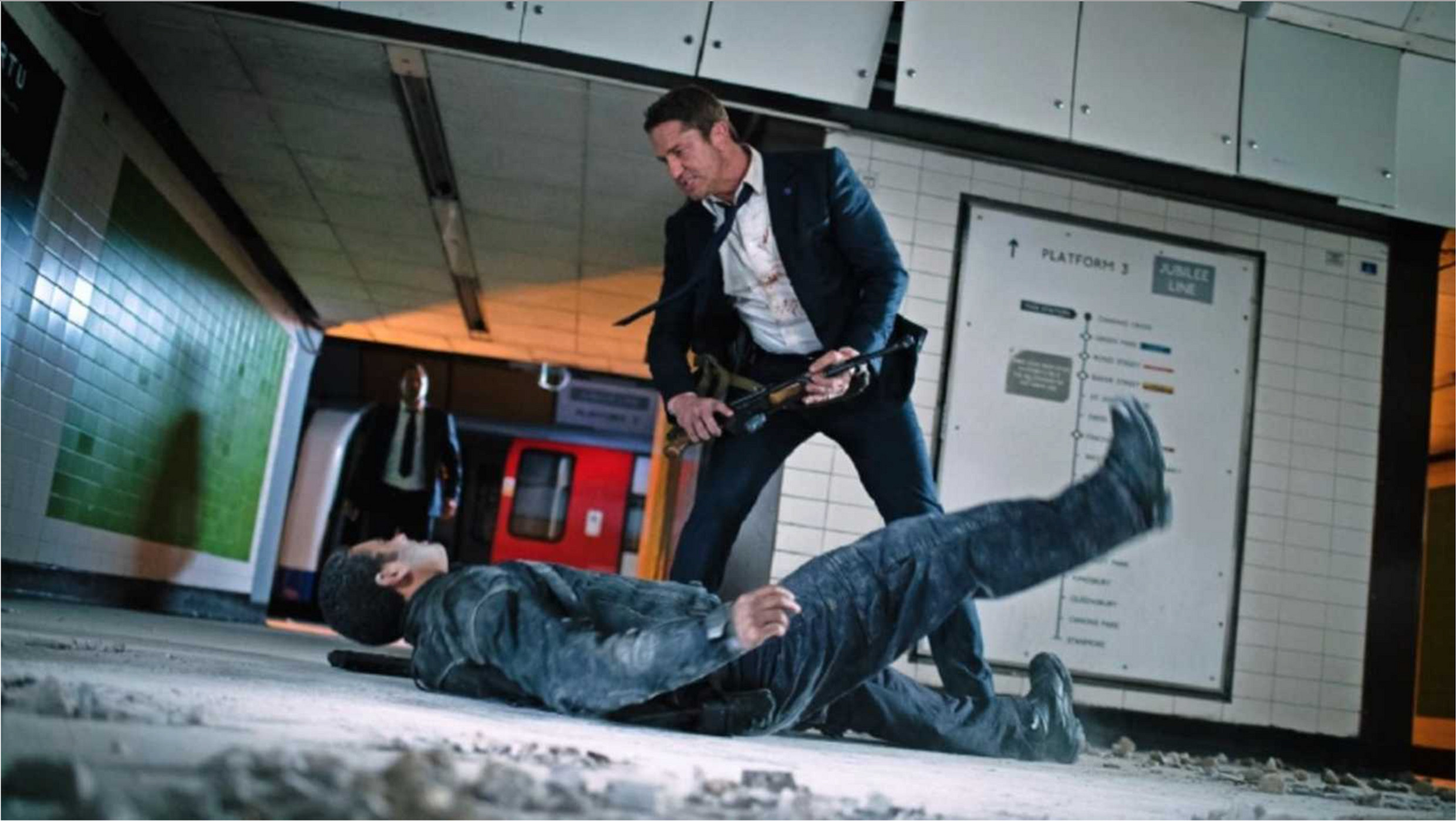

3/5

Tangerine receives 3 bloodied swords for its lack of research, for the exotification of Morocco, and for its one-dimensional Arab characters.