Novel by Camilla Gibb, published by Random House (2007)

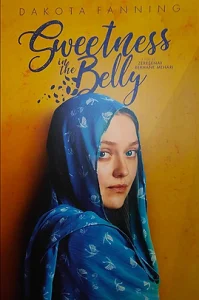

Sweetness in the Belly first came to my attention when an adaptation of the book premiered at Toronto Film Festival, hitting headlines for starring Dakota Fanning as an Ethiopian woman.

Lilly, an English girl is orphaned while living in Morocco in the 1960s and is taken care of by two men – an English Muslim and a local religious figure, who educate her and raise her as an observant Muslim. After travelling overland to Ethiopia, she lives in a remote village called Harar, before being forced to return to England after Haile Selassie is overthrown in 1974.

Told in two timelines, Harar in the 1970s and London a decade later, Sweetness in the Belly is a story that could have humanised a difficult time in an often overlooked country, if it weren’t for one glaring, returning, and continuous problem – the need for a white gaze.

Lilly is more accomplished, more moral, more compassionate than all the Ethiopians around her. It is not the book’s only failure, but it is certainly the most telling. Had Lilly been an Ethiopian woman, many – but definitely not all – of the following problems could have been avoided.

Misrepresenting Muslims

For a novel written by a non-Muslim, more effort should have been made to accurately represent Muslim struggles, rather than drowning them with the author’s own assumptions.

Gibb offers a hairbrained hot-take on how Muslims observe fasting in Ramadan: there are those who are very observant, refusing even to swallow their own saliva, those who try to get out of fasting, but “[m]ost of us linger somewhere in the middle, erring once or twice, which we can make up by fasting sometime later during the year.”

Most Muslims either observe fasting, or do not. Few decide to skip days because the recompense for doing so is so high – not one day’s fast, but sixty days, consecutively.

Gibb describes a hair salon in London which has a private room, “where hijab-wearing women can reveal themselves without shame.” For a woman who doesn’t wear hijab – who isn’t Muslim – to attribute shame to Muslim women, rather than modesty, is disempowering and cringeworthy.

Lilly is staunchly religious when she arrives in Ethiopia, but she abandons this resolve without any inner struggle, as soon as her boyfriend suggests that religion is a set of guidelines. So she drinks alcohol, removes her hijab in front of him, and, as she wakes for dawn prayer, she loses her virginity to him to the sounds of the adhan, because “Life was too short in Africa for this not to happen.” More on that ‘Africa’ slip later.

It’s not that Muslims do not do these things, but a Muslim as demonstrably observant and strict as Lilly would offer some struggle, doubt, guilt, or at least inner thought. But Lilly is a cardboard cut-out of a Muslim, that only has the religious range of her creator, who failed to accurately represent what it is to be Muslim. At one point, Lilly prays in a hospital toilet cubicle. This is what Debenhams changing rooms and utility cupboards were created for, Lilly dear.

By the end of the novel, Lilly is the model Muslim, who picks and chooses from Islam. This is jihad, she tells us, “not a fight against those who are not Muslim, as our imam has started preaching.”

This moral superiority is a running thread.

White exceptionalism

It falls on Lilly to teach local children the Quran. While it might be realistic that few women, or men, were literate in remote villages at the time, Sweetness in the Belly doesn’t exist in a vacuum and authors should exercise the social awareness of their time. To suggest that only a white, English Muslim is able to teach the Quran was at best uncomfortable reading and at worst white saviourism.

Although we meet many Harari women, they all have a tendency for violence or colourism; Lilly is the only compassionate and caring among them. Only she protests against the genital mutilation of two small girls (that she unwittingly paid for). As she runs away from the sight of blood and pain, the Ethiopian women around her are jubilant. “The mothers want to see their daughters suffer,” we’re told.

When one of the girls is infected, her mother implores Lilly to go to the hospital with her. I’m perplexed – is it that Harari mothers don’t care about their children? Or is it that Lilly is exceptional purely for her white skin?

It gets old very quickly how often Lilly is told she’s not like the Ethiopian women around her, “No Harari girl would ever have been so bold.”

Exoticism

Although Gibb demonstrates an awareness of othering and exoticism, and does try to combat these misconceptions, she fails to avoid tripping over common stereotypes herself.

The prologue ends with a puzzling quotation from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: ‘“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”’

Yes, you’d be mad to go to Ethiopia.

Lilly grew up in Morocco and lived in Ethiopia, yet refers to herself as a “white Muslim raised in Africa,” for her parents, “the journey ended in Africa.” A continent of 54 countries with thousands of communities, languages, cultures and traditions. But yeah, let’s go with Africa.

I know it is tempting, but imagery pertaining to veils and deserts is not fresh, it’s cringeworthy. Please, white authors of the world, just stop.

“Unlike the Hararis, I didn’t seem to have the capacity for more languages. They switched between them as easily as if they were changing veils.”

Also, please have some respect for the forethought and manoeuvring required to change veils.

Other passing exoticisms include referring to “these feral children,”and describing someone from an “Arabian family,”– Arabian is a horse or a peninsula, not a people.

Anthropology

While the prose in Sweetness in the Belly is stylistic and lyrical, there is little plot to speak of. About a third of the way through the novel, it dawned on me that this is a study of others, a white window into Ethiopia. The otherness is the plot. Gather round, while we explore deepest Africa.

The novel rests on the whiteness of Lilly, because readers, writers, authors, need a white character to identify with, the fact that this novel has been turned into a major movie confirms this.

And the desire to fulfil this need consistently undercuts what can be, at times, a novel with real heart.

I later discovered that the author had a “cross-cultural affair with a local doctor”while in Ethiopia, and this information made me reconsider the author’s intentions somewhat. Perhaps she was inserting herself into the novel, rather than the white gaze. I don’t think it matters much, because either way, the result is a story about the Ethiopian communities in the run up to the coup and civil war, being told by a white outsider. And it is that white gaze which is considered to add value to this story. Because had Lilly been Ethiopian, international movie studios would not be optioning this story for film.

There is nothing about Lilly that requires her to be white, nothing but the prevalent belief that stories of people of colour only have merit when they’re told by – when they’re confirmed by – a white protagonist.

Sweetness in the Belly receives two bloodied swords for exoticism, and for considering its representation to be nuanced.