Novel by Jenny Ashcroft, published by Sphere (2016)

Another day, another white heroine in ~Arabia~, this time, 22-year-old Olivia Sheldon, searching for her lost sister in 1890s Alexandria, Egypt.

Beneath a Burning Sky does offer Arab perspectives, chiefly, from an Egyptian woman, Nailah, who fears her male relatives, looks after her young cousins, and knows what happened to Olivia’s sister.

We know we are supposed to care about Nailah, because she doesn’t wear the hijab, which, according to Ashcroft, most women in 1890s Egypt wear only “to protest against the British rule banning it.” Unlike other Egyptian women, Nailah is clean, modern and moral. And, conveniently, she is always worrying about her colonisers’ wellbeing. Poor Nailah cannot have a moment with her lover or be banished to a harem full of coquettes (oh, yes) without worrying about the white protagonists. Even when Olivia uses her position and race to bully and threaten Nailah, the latter only has capacity is to empathise with the former, reminding us that only white voices matter in this story.

In a passage that betrays the author’s destructive social and racial ignorance, Nailah even wishes herself white for a moment, “She wondered what it would be like to inhabit Ma’am Sheldon’s cream skin, feel that beating pulse, the blood within her, wear those sculpted features and strange eyes.”

The presentation of Egyptians frequently descends into Orientalist and racist tropes. Apart from whitespirational Nailah, Arab women are unlikeable – they neglect their families, they are cruel – snapping the necks of chickens – and they are dirty and unhygienic: “black-toothed matrons lounged, flabby arms stretched behind them, revealing thick clumps of damp hair.”

For its flaws, Beneath a Burning Sky, offers a real sense of its era, chiefly because the characterisation of Arabs is truly Victorian. Arabs are infantilised by the British – even by our heroine, who is ostensibly morally superior to her compatriots. They are knowingly exoticised, without awareness of the impact of this dehumanisation, “His dark head was bare, hair shining, the sleeves of his white tunic were rolled up to reveal muscular arms; so exotic it was almost obscene.”

In short, Arabs in Beneath a Burning Sky, are erased of any semblance of authenticity. Barely a conversation passes between two Arabs where they do not discuss the British characters; they exist solely to further the white characters’ arcs. They are co-opted into their occupation, postulating on the evils of Egypt, and the virtues of Empire in a caricature of the “pleasingly humble and grateful,” occupied Arabs that the author, and society, is so keen to invent.

The novel offers a skewed rewriting of colonialism without attempting to engage with the political climate or complexities of the time.We are simply told that, “For every local who resented the heavy hand of the Empire, there were three more too glad of their jobs and wages to protest.” We hear of the sins of the Egyptians, but nothing of their subjugation by the British. “He never wants to serve with Egyptians again. A band of nationalist soldiers took against him in the early eighties, when he refused to help them in an uprising. The men locked his wife and children in a hut and set fire to it. I tell you, Olly, there’s evil on every side…”

Though we never hear of this British evil, plenty of page space is afforded to an exoticised Egypt/ ~Arabia~ .When it came to choosing Egyptian names, the author decided, rather than do any research, she would just invent them! So much easier :DD. That’s how we end up with the pearls of Babu, Kafele, Jahi, Garai, Tabia, and (oh, God) Cleo. And then there’s the toe-curling Arabic mistake of, “your umi,” meaning, “your my mother.”

This lazy writing would not be accepted in any other area of literature. Nobody writes novels about England and thinks it is sufficient to invent character names, and no publishing house would allow it either. The continued exotification of ~Arabia~ is what perpetuates this lazy attitude towards accurately capturing real, complex and diverse Middle Eastern countries.

In fact, it’s hard to believe that this misrepresentation wasn’t the intended outcome, no effort is spared in the quest to otherise Egypt, which is more dangerous than Britain, where people are more evil than the British, “You cannot know the dangers of this land, the things people do.”

The result is a distorted, racist approximation of the elusive ~Arabia~ that pretends to lend complexity to Egyptian voices. But there is not complexity here, no Egyptians, and no authenticity.

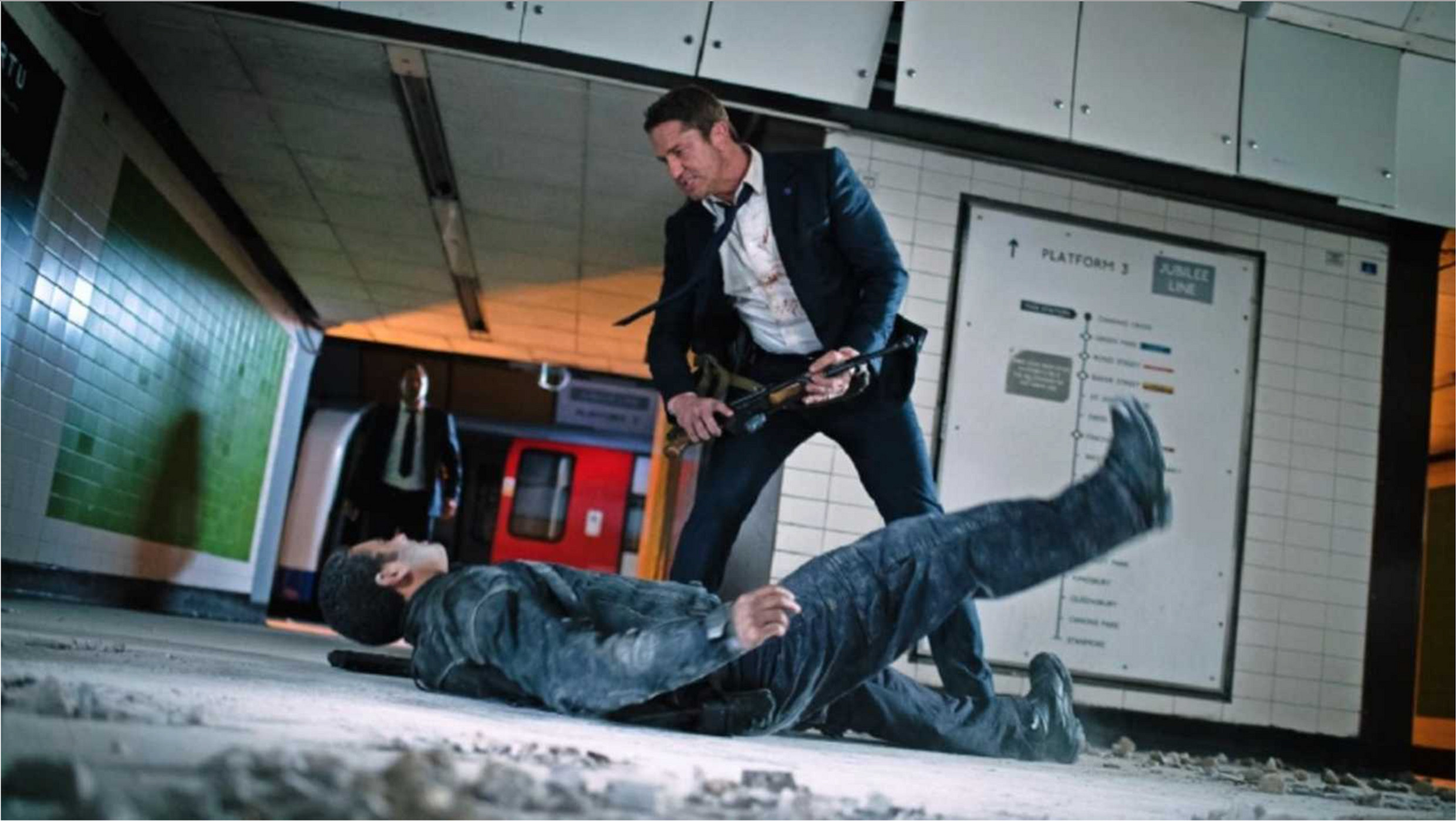

3/5

Beneath a Burning Sky receives 3 bloodied swords for its lack of research, for the exotification of Egypt, and for its one-dimensional Arab characters.