TV series (Season 1, 2018)

On first impression, this Spanish series seems to promise nuanced Muslim characterisation, and a dramatization that challenges the racism that Arabs face in Spain. Elite is set on two timelines – the lead-up to, and aftermath of a murder of one the students at a prestigious high school. One of the principal characters, and suspects, is Nadia, is a Muslim, hijabi who is religious and intelligent. Her brother, Omar, is gay, which might seem like a fresh storyline for a moro until you realise that he is also, predictably, the local drug dealer.

I’m not sure if the bar is so low that we must be grateful for Muslim characters that are not terrorists, but if we are, then I suppose this show gets a begrudging second of applause. But for all the promise of nuance and complexity, Nadia and Omar’ stories end up reinforcing the stereotypes the creators presumably set out to avoid.

Reinforcing Islamophobia

Nadia’s story begins with her school demanding that she remove her hijab or face expulsion. She reluctantly agrees, but continues to face a neverending barrage of racism and microaggressions. She is called “a fundamentalist,” “Taliban,” and even her friends accuse her of planting a bomb and speak to her in shockingly racist garbled imitations of Arabic.

All of these offences are believable and relatable, and with proper execution they could have been a brilliant, astute social commentary. But Nadia never receives any justice, the racism she faces every day persists unchallenged. Simply regurgitating prejudice without any retribution, change or social commentary is not clever or nuanced – it just perpetuates and normalises racism.

Nadia is constantly apologising to her schoolmates for minor transgressions, but not one of them ever apologises to her for racism. Clearly the creators of Elite have never been subjected prejudice; how privileged to think that Nadia is happy maintaining friendships with racists.

In fact, the writers seem to get some macabre joy in subjecting poor Nadia to cruel and inventive Islamophobia, without having anyone, including themselves, challenge it.

Unless, perhaps, the fact that white man falls in love with her, despite her defects. Maybe that is what is supposed to signal Nadia’s merit.

It’s an embarrassing ‘love’ story. Despite Nadia repeatedly telling Guzman to leave her alone, he constantly ignores her wishes, visiting to her parent’s shop and her place of work (pursuing her only as a bet, orchestrated by his Islamophobic girlfriend).

Although Nadia is fiercely pro-hijab, when she is involuntarily drugged at a party, she starts to pursue Guzman.

She goes swimming in his pool, her headscarf falls away in horrifically Orientalist (and just unrealistic) imagery. As her hijab slips off, so too do her religious inhibitions that have been holding her back. Her plaited hair is miraculously loose and flowing. She says “I’ve never felt better.” Finally, now that she is drugged, Nadia is free to act as she truly desires. The camera pans out to the hijab at the bottom of the pool. There is no subtext here: Muslim women need to be forcibly liberated, because deep down, if we were capable of free thought, we’d all be gagging for a white man.

But honourable Guzman – who knows she has been drugged – doesn’t take advantage, and the shows sees fit to equate not raping a woman with being a “gentleman.”

“I had you in my pool, ready for anything and I didn’t touch you… I could have taken advantage, but I didn’t.”

In fact, Elite’s creators cut out a kiss between Nadia and Guzman in this scene. So no, Guzman does not get any awards for being a caballero hero.

Arab stereotypes and misrepresentation

And then there’s Omar. For all the nuance that could come with being a closeted Muslim, Elite chooses, instead, to use him as a tool to highlight how backward, and intolerant his Palestinian father is. Of all the students, parents and teachers in the show, the only one to object to homosexuality is the angry Arab father who runs a grocery shop. He’s “a caveman” who punches things; he can’t control his temper, he grabs his daughter to pull her out of an exam and he slams his son against the wall. “Too much liberty,” he says, “but no more.”

The Spanish parents, by contrast, are head teachers and wealthy businesspeople who are open-minded and caring.

There are problematic representations galore. Omar wasn’t clever enough to get into the Elite school with his sister, which is used to explain his drug dealing.

When Guzman wishes to apologise for attempting to take Nadia’s virginity in order to mock her, Nadia demands that he “Ask for forgiveness, Muslim style…ask for leniency on your knees.” Nowhere is it made clear that this is not a thing.

Two seconds after suggesting tea with another Arab family, Omar’s father tells him, “Do you have something better to do than meet your future wife?” Again, nobody speaks like this. Declaring someone your son’s future wife before he’s even met her is not a thing. Maybe it is what Spanish/ Argentinian writers think is an Arab thing, but, you know, maybe check before you write it into a show on Netflix?

And then there’s Nadia’s clothes. She makes sure to put on her hijab as soon as she leaves school – it’s clear that her school forced her to remove it against her will. We’re supposed to believe that her parents are extremely strict, but she wears transparent hijabs and clothes and is always touching Guzman in front of her parents.

While Muslims are diverse – some are devout and others nominally Muslim – there needs to be some consistency and believability when representing these characters. Either Nadia’s parents are strict – meaning no touching, no transparent clothes, at least in front of them – or they are more relaxed – which they are demonstrably not, given her father’s (frankly tiring) obsession with control.

The show goes to great lengths to vilify Nadia’s father for his strictness. He gets angry when he learns that Nadia removed her scarf to remain in school, the story completely neglects the fact that the school forces Nadia out of her clothes. Much like the racism Nadia faces, her oppression by the school is glossed over as a reality that model Muslims just have to deal with. Much more oppressive than banning the hijab, we must surmise, is having a father who loses his temper when he finds out.

Not every Muslim character must exist to break (or, worse, perpetuate) stereotypes. Can we just have coincidental Muslims whose whole story isn’t based around breaking free of their identity? Elite’s creators, in attempting to show complex Muslims that go beyond the terrorist/ subservient dichotomy, dug the very pitfalls that they presumably sought to avoid. The result is a pair of characters that are confusing, contradictory and that lack proper resolutions.

Omar is still a drug dealer hiding from his father, who is still an angry man who is trying to marry his son off. Though Nadia ends the season slightly more empowered against her father, she is still oppressed by her school and her classmates, which we presumably don’t care about.

I’d like to see a Nadia who is true to her intelligence and convictions – who subverts the hijab ban by wearing the – permitted – school swimming caps. Although Elite clearly intended to offer a more complex characterisation of Muslims – and, indeed, that warrants some acknowledgement – the result is production of the white gaze; a mish-mash of poor characterisation, problematic stereotypes and normalised racism, interspersed with occasionally defiant and believable Muslim voices.

2/5

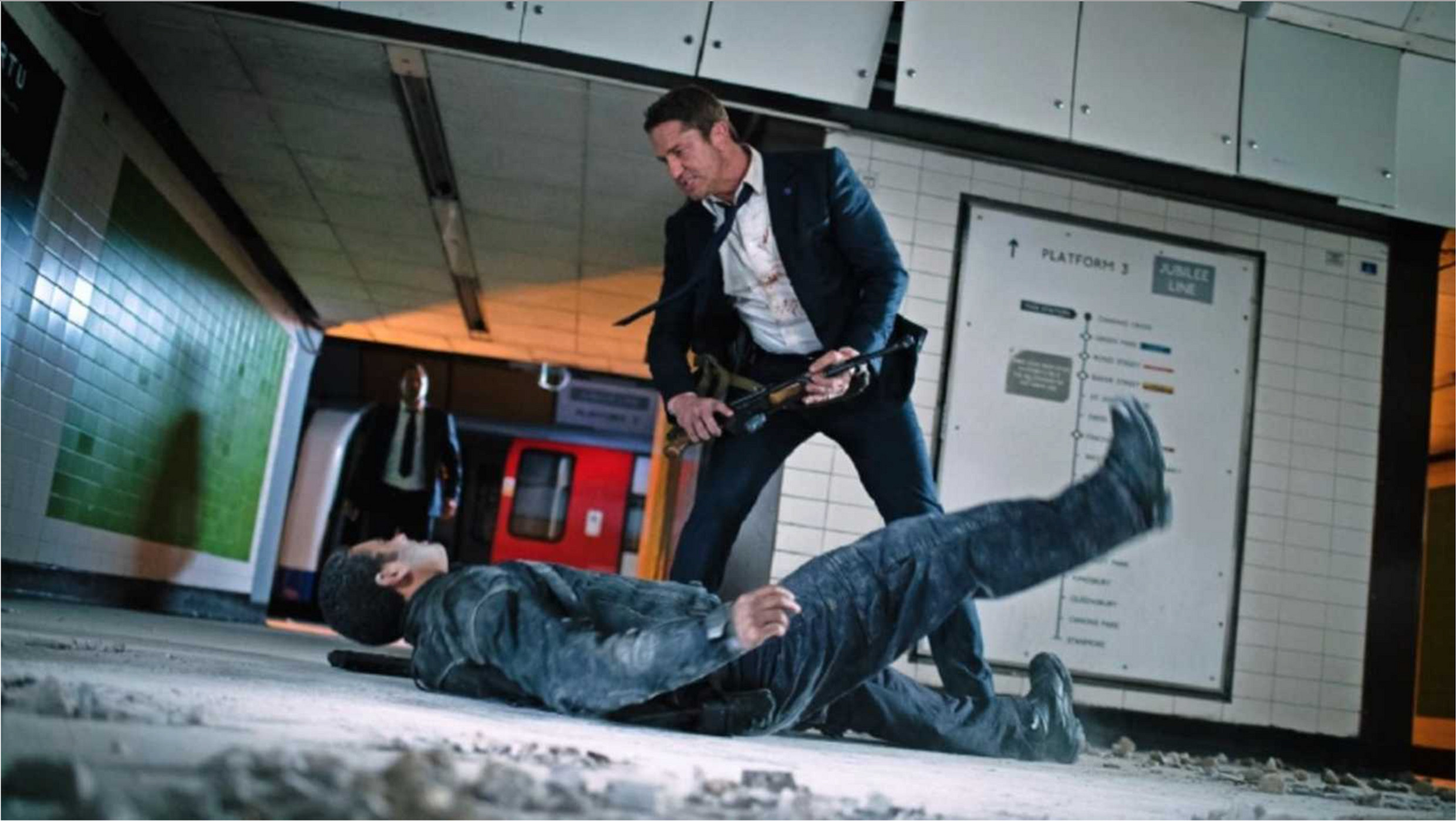

Elite receives two bloodied swords for its lack of research and false complexity.

Soy hispanohablante. This film was watched in Spanish, with Netflix’s English subtitles used for quotations.