It’s a battle between the heart and mind when it comes to Aladdin. Of course, we all want to see people who look like us, with names like ours, represented on the big screen, especially in roles that are more challenging than Terrorist Number 3.

But is the homogenization of the Middle East, North Africa, India and China really a representation we can stand by in good conscience? Can we accept Genie’s carriage-sized turban exploding, because at least it exploded with confetti, not C-4? Is this how low the bar is?

Sure, the cast is almost exclusively people of colour, which is something to behold. But the director, Guy Ritchie, producers and writers are almost all white men; take a look at any behind-the-scenes photo for a jarring realization that the diversity is limited to on-screen roles.

And it shows. For all their attempts to shake its predecessor’s stereotyping, Aladdin is still the exotifying, Orientalist, flattened version of what a white man dreams up about ~Arabia~.

Perhaps it’s not entirely their fault. Unlike other Disney films, whose power centre around, and depend on, our heroine’s enchanted hair, or magical icy powers, or her status as a mythical being – the story in Aladdin rests on the mystical, exotic, magical status of an imagined ~Arabia~.

That’s why, in the opening song, we’re encouraged to get, “lost in a trance of another Arabian Night.” From the outset, we are told that this story is set in an iteration of Arabia that we are comfortable with, not one that resembles any reality, “This mystical land of magic and sand is more than it seems.”

Unfortunately, we spend the entire film subjected to magic and sand, and never have a chance to peek at the promised reality.

Why are Arabic names still anglicized? Is it too authentic to have a heroine called Yasmin, a hero who can pronounce (either of) his own name(s), or a monkey who isn’t called Dad. Would it have been so hard to say dhuhr prayers instead of “midday prayers”?

And in what world to two people meet “When the moon is above the minaret?” It’s not just exotifying, it’s also impractical. Which minaret? How far above? From whose perspective? So many questions.

This sets the tone for the entire film; it doesn’t matter if things don’t make sense, so long as they sound passably Arab.

When Jasmine doesn’t want to marry a suitor, her handmaiden, Dalia (hooray, an Arabic name pronounced correctly) tells her, “You’re just getting married; it’s not like you have to talk to him,” because, of course, that’s how Arab marriages work.

The good/bad Arab dichotomy

The white-centrism of this movie is also reflected in its inability to shake the good/bad Arab dichotomy. Our heroes, Jasmine, Aladdin and Genie are culturally Western; they speak like Americans, they value independence and altruism, and they love the undeserving townspeople of Agrabah, who, by contrast, won’t feed hungry children, who want to chop off a woman’s hand and cut open a homeless teen for stealing bread. The ruthless townspeople are dark-skinned, bloodthirsty and have foreign accents (actually it’s the poor street-rat Aladdin who, puzzlingly to nobody, has the foreign accent).

And then there’s Jafar, who thinks women should “Stay silent,” and who wants destroy cities and kings to create an empire. Yes, a story has to have an antagonist, but did he have to be such a stereotype of an Arab man?

So why can’t we just create a fantasy land of Agrabah and just enjoy it without people like me raining on your parade (incidentally, the Prince Ali parade song was the most awkward detergent-commercial of a scene, and my eyes can never unsee just how uncool Will Smith can be)?

Because perceptions matter. This Aladdin is even more powerful than the 1992 classic because as a live action film, it presents Agrabah as a realistic city with a real culture.

Homogenisation

Frozen’s city of Arendelle is named after Arendal, near Oslo. The town in Beauty and the Beast is inspired by two Alpine villages, Riquewihr and Ribeauvillé. The Little Mermaid is set off the east coast if Denmark’s Jutland. These films were still huge successes without resorting to the misrepresentation of their nations.

But Arab cultures are not worthy of precision or accuracy. Julie Ann Crommett, Disney’s VP of Multicultural Engagement, said that Aladdin, “very much reflects a mixing or association of different cultures in a broad region that you can consider the Middle East slash South Asia and even to China actually by extension, so really the Silk Road.”

I’m calling camelshit. The homogenization of these vastly different and distant regions was for convenience, not for authenticity. Agrabah is clearly intended to be an Arab, Muslim-majority city, but one that has been stripped of all of its culture and religion and replaced with cherry-picked elements from other cultures to create an Orientalist dream-version of ~Arabia~.

This is a trend that is repeated incessantly in novels, with the creation of invented cities. When you set a story in a city that doesn’t exist, you release yourself of the responsibility to represent it accurately. But the world doesn’t get the memo, and the stereotypes that 1992’s Aladdin perpetuated are being regurgitated yet again, and we’ll be plagued with a vague approximation of what the Middle East is for another 27 years, no doubt.

Aladdin still has all the damaging key ingredients of the original – costumes that are a hodgepodge of different continents, presented as a homogenous; American characters to root for, and foreign characters to hate; coquettish giggling girls and sweeping desert scenes. There’s even a jagged, Arabesque font that dissipates into sand.

And then they threw in this identity crisis of a dance number for good measure.

The success and appeal of Aladdin is predicated on the misconception that the Middle East is mysterious, dangerous, and magical. While that may not seem damaging in a children’s film, it perpetuates the destructive stereotyping and alienation of Arabs. It’s why I can’t pick up a book set in the Middle East (and written by outsiders) without being subjected to desert, souq and veil metaphors, and writers thinking its fresh to say things like camelshit when they mean bullshit.

Give me an Aladdin that’s not stripped of Arab identity, that’s not manufactured around what America thinks the Arab world looks like, that doesn’t yield to stereotypes about innately violent Arabs.

But deprive this film of the layers of exoticism, othering and Orientalism, and you’re left with something unrecognisable; a story about an ordinary Arab boy. And nobody wants to see that film.

3/5

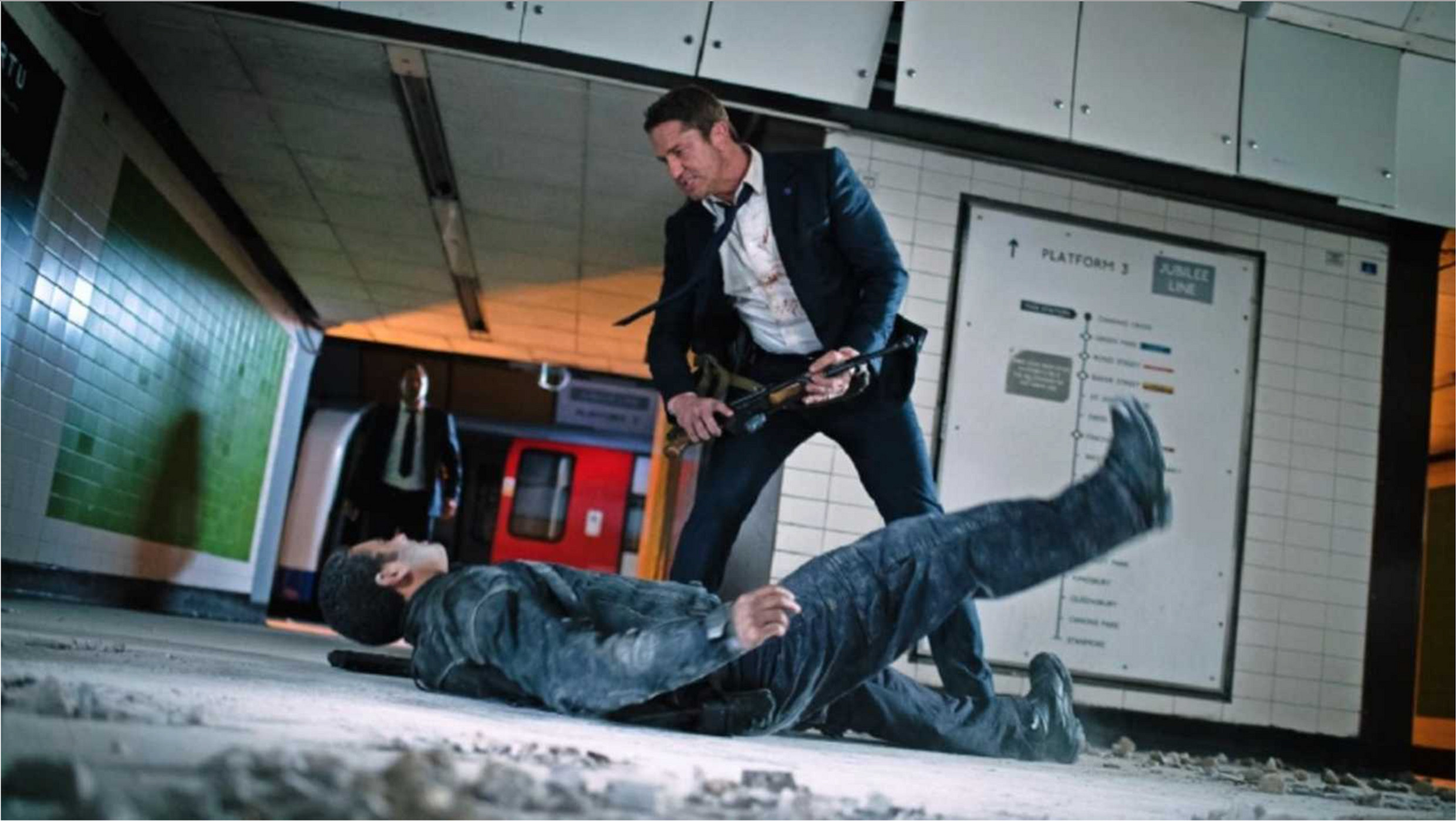

Aladdin receives 3 bloodied swords for its lack of research, for the exotification of the Middle East and for perceiving itself to have avoided stereotypes.